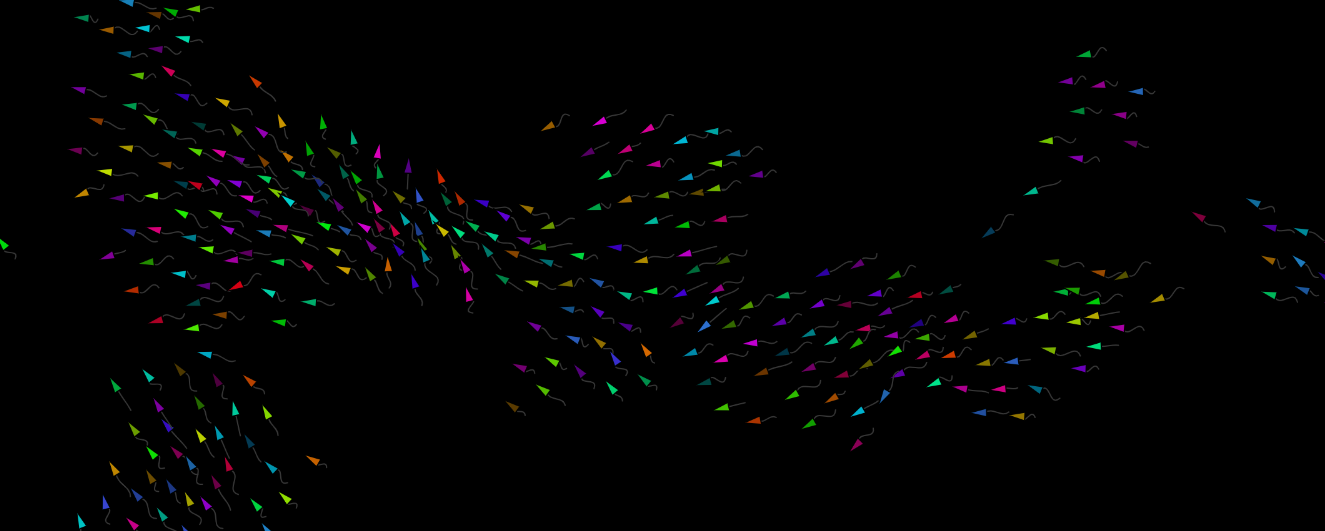

Flocking Ecosystem

If we reduce life to its most essential components, exploring the multiverse of possible interaction mechanisms becomes more intuitive when viewing each part of the whole as a simple set of binary rules.

The Sketch

Swarming behavior is a pattern familiar to everyone with a pair of eyes and which we can easily recognize in a flock of birds or in a school of fish, that’s why it’s called Flocking algorithm. The truth is that this complex behavior can arise from three simple orders that govern each individual of the simulation: a point entity (or Boid) in a 2D space with a velocity vector assigned and is only aware of its close vicinity, as well as the velocity vector of its neighbors. These three orders to rule them all are:

- Separation : Avoid crowding neighbors (short range repulsion)

- Alignment : Steer towards average heading of neighbors (align the velocity vector)

- Cohesion : Steer towards average position of neighbors (long range attraction)

Steering is applying an acceleration vector, which is a result of polling the positions and velocities of the near neighbors, to the actual velocity of the boid. All the boids follow these instructions in an infinite loop, updating steer, velocity and position values according to their current vicinity.

When dozens of boids are left to wander a 2D space with periodic conditions, they start forming swarm-like groups that move coherently. There can be many swarms in the space and furthermore, these groups are not stable in population since colliding groups or swarms that pass near enough may change the group dynamic.

This kind of behavior and rules have been studied for decades: it has been studied as flocking in multiple scenarios, dimensions and rule variations. The original architecture of the flocking algorithm I used is based on the one developed by Daniel Shiffman in a video about it.

Flocking behavior was simulated on a computer in 1987 by Craig Reynolds with his simulation program, Boids. This program simulates simple agents (boids) that are allowed to move according to a set of basic rules. The result is akin to a flock of birds, a school of fish, or a swarm of insects.

– Wikipedia

My contribution to the algorithm with which this sketch works consists of special boids that have the ability to change an internal state of normal boids, these special new boids are going to be called Shifters, since they shift their neighbors. There are three types of Shifters:

They freeze boids (or reduce their mobility) and turn them blue, allowing them to create connections with other nearby blue boids. This makes it look like the knitter is knitting a net. heal infected boids (red or blue). They can steal speed from nearby boids.

- Flockers: They infect boids by turning them red and more strongly linked to other red boids. This causes them to behave as a tightly bound unit.

- Knitters: They freeze boids (or reduce their mobility) and turn them blue, allowing them to create connections with other nearby blue boids. This makes it look like the knitter is knitting a net (pun not intended).

- Healers: They heal infected boids (red or blue). They can steal speed from nearby boids. They may also switch velocities direction (but not magnitude) with a boid while interacting with it.

Shifters do not like to interact with shifters of different species, but interact normally with same species shifters and other boids. They have a contagion probability associated, which means that not all interactions will result in a contagion.

Flocker capturing healthy boids, increasing their maximum speed limit.

FLocker

Knitter creating a network of static boids.

Knitter

Healer liberating some boids form a knitter's net.

Healer

The Purpose

Since I knew what programming is, I have learned a few interesting concepts here and there, but over time and reviewing the development that my sketches have led, I have noticed something quite obvious now: I am low-key obsessed with random behaviors and the emergence of complexity. The flocking algorithm is characterized because it precisely achieves this task: to represent an aggregate, complex and organic behavior that arises from individuals following simple rules and interacting in the same space. And well, it has been known for a long time that it is beautiful and that it seems like happy little birds and fish moving in a group, but only doing that can not escalate more when it comes to complexity and can not give birth to unexpected behavior. The flocking simulation is a wonderful concept in the study of the reduction of natural phenomena through programming, but it also leaves you with a mouthful of so many potential uses that just sticking with the original rules would be a waste of time.

I hope that the proposal will generate new discussions around the organic behavior of autonomous agents with simple programming. There are perspectives that reconcile programming and logic with nature and all its splendor, and generating a dialogue about it is the first step in asking the right questions that point in more interesting directions.

The Result

With the introduction of the new boids, new parameters are added to the simulation and therefore the behavior grows in complexity. When I did the first experiment I was surprised because, despite not knowing what to expect, I found new behaviors that my human perception was able to recognize and that, unless they are products of my volatile imagination, represent a new way of adding complexity to the system. A few insights of what can be noticed at a glance:

- Flockers and healers can each form groups of boids around them, moving as a group that can affect more boids. Despite the fact that flockers and healers cannot interact with each other (and even repel each other a little), certainly the groups formed by these can be brought together in larger groups where boids, flockers and healers coexist, using cohesion with the normal boids as a force that counteracts the aforementioned repulsion. I like to think of this scenario as a reduced case of symbiosis.

- knitters freeze boids that, if they are very close to other frozen boids, are connected between them with a line (the connection or lack of it does not affect the simulation at all, it is just a visual element). When solitary moving boids (healthy or infected by flockers) pass near these nets they naturally try to react at the speed of their neighbors. These, when stopped or moving very slowly, cause the boid to stop as well, being trapped by the static influence of the network.

- Knitters usually stay near the net as an effect of the net static influence, but not always they remain static as trapped boids. They keep moving in the net surroundings until a boid gets near enough to interact and modify the knitter velocity. This perturbation, in addition with the aligning force present in every boid, causes the knitter to stop being dormant and ‘Hunt’ new boids that get stuck in the near net. Sometimes perturbations in a far point in the net are propagated due to the proximity of the net boids between them, causing the dormant knitter to react even if the new boid is trapped not so near.

-

Healers may pass through small healthy groups of boids, even using its boids to catapult themselves forward by stealing speed. Bigger groups catch the healers easier and since it usually swaps speeds with his neighbors, having a healer within the group usually helps keeping boids aligned in the same direction. This feature also represents formation of larger groups when there are flockers and healers within the group, since flockers are more likely to separate form the group due to weak aligning.

The Controls

DRAG the cursor through the screen to generate new neutral boids pointed in random directions.

- F : Creates Flocker in the cursor current position

- H : Creates Healer in the cursor current position

- K : Creates Knitter in the cursor current position

Mobile

- TOUCH AND DRAG to create new boids.

- SHAKE device to create random shifter in random XY position.

Latest Release

Latest commit : 13 / apr / 2020